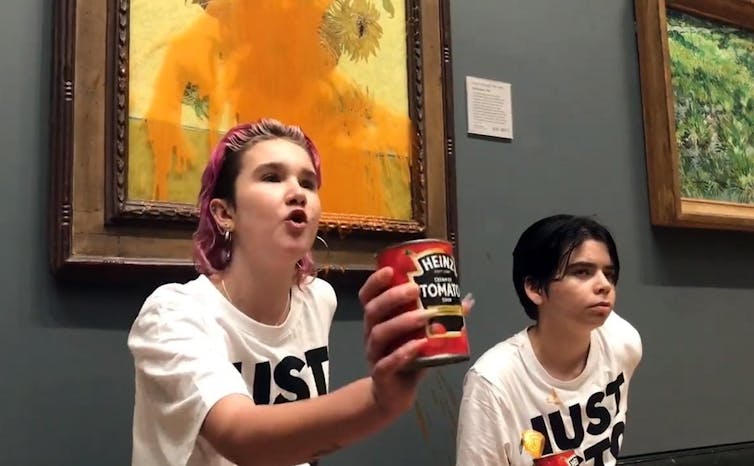

Climate activism has been on a wild ride lately, from the shock tactics of young activists throwing soup on famous paintings to a surge in climate lawsuits by savvy plaintiffs.

While some people consider disruptive “antics” like attacking museum artwork

Climate activism has been on a wild ride lately, from the shock tactics of young activists throwing soup on famous paintings to a surge in climate lawsuits by savvy plaintiffs.

While some people consider disruptive “antics” like attacking museum artwork with food to be confusing and alienating for the public, research into social movements shows there is a method to the seeming madness.

By strategically using both radical forms of civil disobedience and more mainstream public actions, such as lobbying and state-sanctioned demonstrations, activists can grab the public’s attention while making less aggressive tactics seem much more acceptable.

I study the role of disruptive politics and social movements in global climate policy and have chronicled the ebb, flow and dynamism of climate activism over time. With today’s political institutions largely focused on short-term desires over long-term planetary health, and global climate negotiations moving far too slowly to meet the challenge, climate activists have been reconsidering their tactics – and radically rethinking how to make their activism most effective.

In meetings with global activists in recent weeks, my colleagues and I have noticed a shifting emphasis to local climate battles – in the streets, political arenas and courtrooms. The lines between reformists and radicals, and between global and grassroots mobilizers, are blurring, and a new sense of strategic engagement is taking root.

When global institutions fail the public

Activist groups have long relied on a strategy known as the boomerang effect – using international networks and global institutions such as the United Nations’ climate talks to influence national governments’ policy choices.

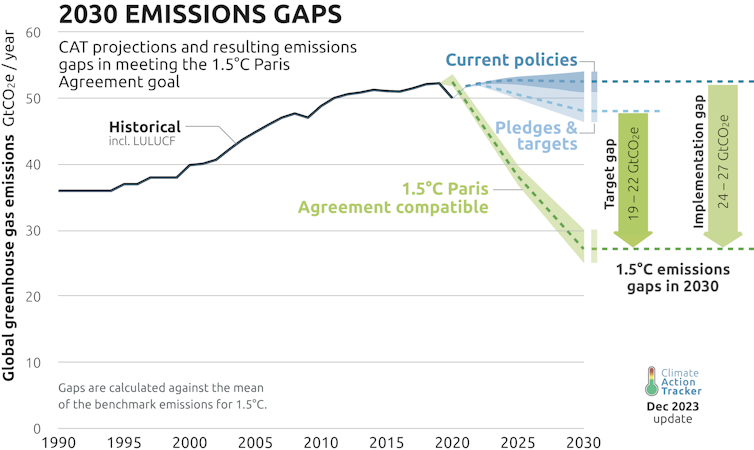

But while this tactic was initially well suited to climate change, results show the talks have been too slow and insufficient. The growing influence of the fossil fuel industry, whose products are the leading cause of global warming, has left some activists seriously questioning whether the U.N. climate process is still useful.

The 2023 U.N. climate conference solidified these concerns when the conference’s host, the United Arab Emirates, put its state oil company CEO in charge of the climate talks. Some people argue that oil companies have to be part of the solution. But the conference was overrun by a record number of oil and gas lobbyists more than 2,400 of them. And it was tainted by allegations that it was being used to further, rather than halt, fossil fuel development. The final agreement of COP28 left room for the continuing expansion of fossil fuels.

The announcement in January 2024 that Azerbaijan, host of the next U.N. climate conference in late 2024, would place another oil industry veteran in charge of COP29 put another nail in the coffin of any faith many activists still had in the system.

Climate activists go local

In response to the weakness of global climate negotiations and failing climate policy, my colleagues and I are seeing signs of activists turning more to their local roots. Notably, we are seeing a ramp-up in sophisticated legal battles over climate change.

Over 2,000 new climate change cases have been filed in the past five years. Most seek to compel governments and corporations to reduce their emissions or keep fossil fuels in the ground, and the majority are in the United States. Over half of the cases decided between June 2022 and May 2023 had a favorable outcome for the climate, though most still face appeals.

In 2023, a judge in Montana recognized the state’s constitutional duty to protect residents from climate change. In another case, a court in The Netherlands in 2021 set a precedent by ordering the oil company Shell to reduce its emissions by 45% by 2030 in official compliance with the international Paris climate agreement.

How radical spectacles create space for progress

When radical activism takes place at the same time as formal institutional challenges, studies show the combination can help increase support for more moderate activism.

Researchers call this the “radical flank effect.” It was effective for both the civil rights and feminist movements, and it is evident in other political movements in the U.S. today.

When people are exposed to radical forms of environmental protest, they become aware of the problems. Seeing the extremes can also leave them more comfortable with supporting less extreme tactics.

For example, the idea of throwing tomato soup on Van Gogh’s glass-covered “Sunflowers” painting may have been polarizing, but it got the general public talking about the soup-throwers’ cause – ending fossil fuel use. And that can open doors for political leaders to discuss viable solutions to climate change.

We see this happening in the U.K. After initially disapproving of protests, London Mayor Sadiq Khan met with Extinction Rebellion, a group known for dramatic actions such as spraying fake blood on the steps of the U.K. treasury. Then-U.K. environment secretary Michael Gove met with the climate activists to discuss emissions reductions. Days later, the U.K. Parliament declared a climate emergency – the first country to do so.

Politicians under pressure from climate protesters are shifting course in the U.S. as well. President Joe Biden made climate change a focus of his first campaign, but activists aren’t getting anywhere close to everything they want and have made Biden a recent target of climate protests and even hecklers.

While it is hard to get into the mind of judges and juries, research shows that in cases such as workers’ and women’s rights struggles, radical and anti-government protests can have an impact on them. While court decisions rarely produce radical societal change, they are frequently followed by legislative changes that meet more moderate demands.

The real aim

Criticism of extreme activism often misses a crucial point: The public’s reaction isn’t necessarily the activists’ end goal. Often, their ultimate aim is to influence government and business decision-makers. And while decision-makers are rarely, if ever, going to attribute their actions to activist pressure, the passing of the climate-focused Inflation Reduction Act in a gridlocked U.S. Congress in 2022 and declarations of a climate emergency across the globe suggest climate activists’ concerns are getting through.

When looking at climate activism, pundits should be cautioned in their criticism of what they see as a “disjointed movement.” The perceived madness is indeed method.

USC graduate student Abhay Manchala contributed to this article.

Shannon Gibson is affiliated with the Gibson Climate Justice Lab and Global Justice Ecology Project.