Many of the significant health disparities and inequities[1] Hispanic communities in the United States face are tied to a long history of health injustice in the Hispanic world.

The health landscape of early modern Hispanic societies, particularly from the

Many of the significant health disparities and inequities[1] Hispanic communities in the United States face are tied to a long history of health injustice in the Hispanic world.

The health landscape of early modern Hispanic societies, particularly from the late 15th to 18th centuries, was a complex interplay[2] between professional and nonprofessional providers shaping health care. The convergence of Indigenous, African and European practices, both in Spain and the Americas, affected how clinicians treated their patients.

This all played out against the backdrop of the Inquisition and colonization[3], when the Catholic Church prosecuted heresy. Consolidating religious norms promoted health care through charitable activity, such as the creation of hospitals, but also created challenges between the authority of the Catholic Church and competing health care initiatives.

My research[4] focuses on how health and medical practices in early modern Latin America and Spain are represented through cultural artifacts, including literature, recipe books, the Inquisition and convent records. In our book, my colleague Sarah Owens[5] and I explore how gender norms affected[6] medicine and health care. We also consider how popular representations of health and medicine in culture inform widely held beliefs and biases about these experiences.

Understanding the historical roots of health disparities in Hispanic communities can help address them[7] both locally and globally today.

Interplay of medical practices

Latin America and Spain in the late 15th to 18th centuries were home to a number of medical practices[8], including traditional medical knowledge and remedies and the professionalization of medicine through new universities and licensing systems.

Early modern medical humanists[9], or Renaissance clinicians, took up medical treatises by the ancient Greek and Roman physicians, including those of Galen and Hippocrates, and revived them in the context of “learned” medical instruction through European universities. The study of Paracelsianism[10], or the theories of Swiss physician Paracelsus, though more contested among practitioners because of its connections to the supernatural and occult, also affected a variety of health practices across early modern Spain and colonial Latin America. With the publication of anatomical treatises at the start of the 16th century, including the work of Renaissance physician Andreas Vesalius[11], the study of anatomy slowly and dramatically changed medical practice.

Traditional healing practices varied significantly but often provided accessible and culturally compatible care[13], including reduced language barriers. Many people in Hispanic communities still rely on these practices today. Discussions about the legitimacy and health effects of folk remedies in Latin America, such as varieties of herbal and holistic medicine and other animal-based remedies[14], are ongoing.

Gender and medicine

As health care became more professionalized during the early modern period, some women found ways to practice medicine in more formalized contexts, while others continued to work as healers or herbalists. These practices alternated between success and suspicion[15] during the Spanish Inquisition. Accusations of sorcery and witchcraft along with sexualities outside heterosexual norms often collided with practices of health and medicine.

But just as pregnancy and child–rearing are not the only medical events that shaped early modern women’s lives, women medical providers weren’t only witches[16]. Nuns in Arequipa prepared treatments in convents, and mothers and daughters made medicine within households in Madrid.

From Fernando de Rojas’ 1499 tragicomedy “La Celestina[17],” about the go-between who crafts love potions and repairs hymens, to the 2019 Colombian TV series “Siempre Bruja[18],” about a 17th century Afro-Colombian witch who finds herself in present-day Cartagena, the cultural legacy of witchy women healers in the Hispanic world continues to be deeply felt.

Class, race, geography and language

The transfer of plants, animals and diseases across the Atlantic also profoundly affected health outcomes.

European diseases such as smallpox[19] devastated Indigenous populations[20]. Meanwhile, plants from the Americas offered novel treatments[21] for a number of illnesses globally. Peruvian cinchona bark[22] is a natural source of quinine that proved effective against malaria, a disease prevalent in both Europe and the Americas. Other plants such as cacao seeds[23] found various medicinal and ritual uses, including relieving exhaustion or anxiety or improving weight gain.

But access to this range of treatment methods was unequal, especially across social class and geography[24]. Wealthier nobility in urban centers often had much greater access to scarce resources across the Iberian empire.

Health outcomes were also often linked to racial and ethnic hierarchies[25]. Patients were classified as Spanish, mestizo – mixed European and Indigenous – or African slaves in treatment records. These documents show evidence of uneven access to care, while there is also evidence that some exchanges in care practices across these hierarchies[26] were possible.

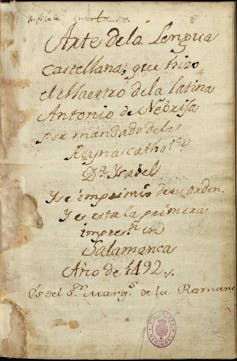

Forced displacement as well as language discrimination also affected health access and outcomes. Spanish wasn’t standardized as a language[28] until the publication of Antonio de Nebrija’s “Grammar of the Castilian Language[29]” in 1492, inscribed to Queen Isabel with the reminder that “language has always been the companion to empire.”

For example, while Arabic and Hebrew were widely spoken throughout the Iberian Peninsula before the forced expulsions of the Inquisition, politics around language resulted in centuries of stereotypes and discrimination against Muslim and Jewish medical providers, who had to navigate alternative licensing methods[30] to practice medicine in Spain and its colonial territories.

Understanding the story of medicine

More than 400 years later, inequities in and commodification of Hispanic health and wellness continue.

Luxury travelers are sold wellness via Mayan purification rituals[31], among other assorted local remedies and practices that can be purchased, marketed and monetized. Wood from the Palo Santo tree, which healers have used for centuries for spiritual cleanings and pain relief, continues to be grown all over the Americas, including Mexico, Peru and Ecuador, and is now bought and sold globally to bring “good vibes[32].”

Considering these early modern health practices and inequities allows for deeper engagement with health care systems today. Informed critical thinking about medicine and health care across disciplines[33] is a powerful way to consider how these histories continue to shape current values and practices, including ongoing disparities in health care[34].

One such discipline is narrative medicine[35]. Using the tools of the humanities, physicians can broaden their view of their patients from simple metrics to human beings with stories to tell. This process involves perceiving and incorporating patients’ personal experiences, valuing narration of the past and recognizing the significance of the encounter between doctor and patient. While much of this research focuses on English-language narratives, cross-cultural and bilingual research in Spanish[36] is expanding the field.

It is estimated that by 2060 there will be more than 111 million Latinos[37] in the United States. Understanding the historical legacies that have shaped wellness and care practices, including the factors that determine care quality and access, can promote more equitable and culturally nuanced health outcomes.